Curator as Middleman. Søren Andreasen and Lars Bang Larsen Interviewed by Zsuzsa László

|

tranzit.hu

Tags: mediation, modernizm

Zsuzsa László: As an introduction to the seminar you held in Budapest, you talked about the theoretical significance of transparent versus opaque[1] spatial, social, and economic structures. I’m wondering if you still consider it a kind of universal paradigm or are these theoretical structures and processes restricted to certain geographical or social fields? Did you feel, for instance, that Hungarian art professionals are using the same international discourse or did you experience any opacity or discontinuity in the participants’ systems of references at the seminar?

Søren Andreasen and Lars Bang Larsen: The question of transparency is central to the work we do together, which is to discuss the configurations of authority in contemporary art, and the way modes of circulation have become highly significant here. When we focus on the figure of the middleman, we thus refer to the agency of circulation and reproduction, and the kind of authority exercised from this position, as a driving force in contemporary art, investigating what kind of value system is structured by this sphere of circulation.

The figure of the mediator received a lot of bad press during modernity as an agent of reaction, but it is not an unequivocally negative or unproductive figure; it is restless and ambivalent, which seems to be characteristic for contemporary concepts of production—or rather, for the contemporary question: can something be produced at all, even signs? Speaking of the issue of transparency it is also important, for example, to look at the mediating agency of discourses which focus on the real (activism, self-organization, intervention, production, truth procedures,[2] and so on). These types of discourse traditionally have an underdeveloped sense of their own mediating agency because they insist for the most part on transparency and operate through metaphors of uncovering or demanding the real, unlike the historical avant-gardes, which prided themselves on radical breaks and new departures. A traditional utopianism is in this respect better at representing the opaque limit between artistic and political representation.

The effect that the counterproductive middleman has typically had is that “somebody else is speaking through me.” This is kind of paranoid, of course, but perhaps a way to articulate local differences by way of self-examination: who is speaking through me, in Budapest? Who is speaking through me, in Copenhagen?

ZL: Do you believe in multiple modernisms or is it just a way to rewrite history from a postmodern perspective?

SA and LBL: When we read the French historian Ferdinand Braudel,[3] it was as if another historical frame was made possible. The development of capitalist culture in Braudel’s work concerns the way material life is organized, suggesting quite another historical timeframe than the discussions regarding modernity refer to, as well as a definition of the marketplace that differs from Marx’s. This is indeed a perspective that opens up to other modernisms, for example if you think of the exhibition Okwui Enwezor curated in Johannesburg in 1997,[4] in which he focused on the spheres of circulation in their historically brutal pragmatism, rather than on modernity as a project.[5] Or in the words of Stuart Hall, “the world is absolutely littered by modernities and by practicing artists, who never regarded modernism as a secure possession of the West, but perceived it as a language which was open to them but which they would have to transform.”[6]

ZL: Is theoretical discourse—on modernity or transparency, for instance—able to mediate actual issues of art, or is it the other way around?

SA and LBL: We regard both theoretical discourse and art as mediatory practices and aim to locate similarities in methods rather than amplify a dichotomy of theory and practice.

ZL: Mediation usually happens not only through mediators (people, subjects) but through various media (e.g., printed or electronic texts). Do you assign any significance or relevance to these, or to such seminars or talks when the personal presence of the speaker renders the communication almost completely unmediated?

SA and LBL: At the moment we think of mediation in almost ontological terms, considering subjectivity to be a sphere of circulation, and unmediated communication is therefore not an option. The nervous system itself is a medium, just like a seminar or a piece of software or language itself. We simply cannot tell the difference.

ZL: There might still be a medium that has special significance in art: the exhibition. Do you consider the exhibition as a historical form that can become outdated?

SA and LBL: No. If so, art would become outdated. Public organizations (collections) of art, whether permanent or temporary, are the most powerful way to circulate and reproduce the cultural function of art.

ZL: Coming back to the mediating subject, do you consider being a curator a role or a profession?

SA and LBL: Both—and a metaphor. The curator is a middleman as such, characterized by unstable and ever changing representations of his or her agency.

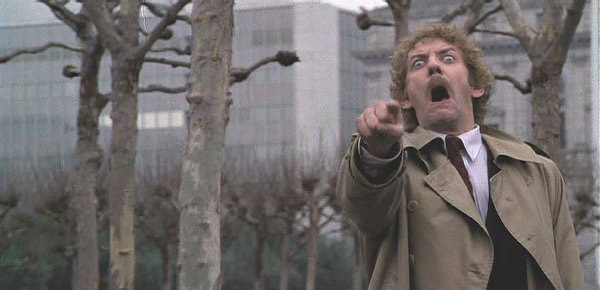

ZL: You talked about another productive metaphor at your Budapest seminar: the zombie and the zombie cult of the ’70s. Am I right to think that the zombie was not only interesting in the ’70s but, probably after having undergone some metamorphosis, is still a living—current—metaphor?

SA and LBL: For the time being we have an experimental attitude towards historical time, based on configurations of death[7] and alienation in a period from the late 1960s until today. Pop culture’s zombie cult was, and is, a North American phenomenon, and in that context the zombie is more alive than ever—where it has a long tradition of being used as social commentary (in the 1960s, against the racism of the American society; in the 1970s, against consumerism; and so on).

Apart from that the zombie is a case study that opens up to many fronts in contemporary culture. Broadly speaking it is a captivating image of cultural cannibalization, and the zombie’s troubling mobility can be seen as a critique of the abject logistics of globalization (logistics for logistics’ sake), just as the zombie embodies the hunt for our brains and imagination in the knowledge economy. In terms of visual art, we now seem to be in a situation similar to the late ’80s and early ’90s, when metaphors of the death of art abounded: apart from attempts at bypassing artistic discussion through politicization or relativizing different kinds of cultural production, we see a renewed interest from artists and curators in metaphysical issues—as if we are looking for the spirit of art.[8] It is also interesting to apply the fundamental ambiguity of the zombie as the living dead to theoretical discussions of biopolitics.[9]

The interview was conducted June-September 2007 via email. Footnotes added by the interviewer.

***

Zsuzsa László is a researcher, curator and board member of tranzit .hu, Budapest. She is doctoral candidate in Art Theory at the Eötvös Lóránd University, Budapest. She has recently co-curated various tranzit. hu projects such as “Art Always has its Consequences” (2008-2010), “Parallel Chronologies” (2009-), and “Regime Change – Incomplete Project” (2012-), “Creativity Exercises” (2014-).

[1] In a semiotic sense, transparency can mean that the signifier (the vehicle of meaning) is dissolved in its meaning, for instance when the meaning of an utterance is so obvious, that we do not even notice the individual words, and the sounds/letters. Speaking of systems, transparency can also mean an invisible structure, one in which we are not aware of the underlying mechanisms producing and structuring phenomena, since these seem self-evident. On the other hand, transparency in this case is not only a synonym of translucence but can be that of perspicuity, or clarity, which is realized when those underlying structures and mechanisms are visible and comprehensible. Because of this contradiction the opacity (visibility) of the signifier in poetry for example and the structural transparency in architecture are equally typical of modernism. Cf.: Anthony Vilder, “Transparency,” in The Architectural Uncanny (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1992), 217–26.

[2] According to Alain Badiou, truth does not appear independently in itself, it is constructed in the efforts and situations that are to grasp it. Badiou identifies four truth procedures: Art, Science, Love, and Politics.

[3] Fernand Braudel (1902–85) was a French historian who studied historical processes through the particularities of everyday life and economics.

[4] “Trade Routes: History and Geography,” Johannesburg Biennale, 1997. Co-curators: Gerardo Mosquera (Cuba), Hou Hanrou (China/Paris), Yu Yeon Kim (Seoul/New York), Octavio Zaya (Spain/New York), Kelly Jones (USA), and Collin Richards (South Africa).

[5] See Jürgen Habermas, “Modernity: An Incomplete Project,” in The Anti-Aesthetic: Essays on Postmodern Culture, ed. Hal Foster (Port Townsend, WA: Bay Press, 1983).

[6] Stuart Hall, “Museums of Modern Art and the End of History,” in Annotations 6: Stuart Hall and Sarah Maharaj, eds. Sarah Campbell and Gilane Tawadros (London: Institute of Visual Arts, 2001), 8–23.

[7] See Roland Barthes, “The Death of the Author” (1967), in Image, Music, Text, trans. Stephen Heath (New York: Hill and Wang, 1977).

[8] During the seminar, two 1992 exhibitions—“Helter Skelter: L.A. Art in the ’90s” curated by Paul Schimmel, “Post Human” curated by Jeffrey Deitch—were mentioned in connection with the zombie cult in art.

[9] This refers to the political aspects of agriculture, gene engineering, plastic surgery, biological weapons, birth control, food technology, etc. The expression was coined by Michel Foucault to describe the practice of modern states and their regulation of their subjects through “an explosion of numerous and diverse techniques for achieving the subjugations of bodies and the control of populations.” The History of Sexuality, Vol. I, 140.