How Art Becomes Public

This essay is an attempt to draw up a chronology of exhibitions and events that in the sixties and seventies redefined the relation between art and the public. We present textual and visual documents of sixteen legendary events from Hungary between 1966 and 1977—the turning points of Hungarian exhibition history. Through these case studies we investigate how innovative models were introduced into exhibition making, what kind of alternative presentational formats were developed, and how legendary events were preserved and revisited in the collective memory of the Hungarian art scene. As a starting point we address the genre of chronology, an important channel for mediating the art events of an epoch. Chronologies play a defining role in transforming atomized events into histories and canons, especially in the case of East European art events that often happened in the “second publicity”[1] during the ’60s and ‘70s. During our research on chronologies we encountered several rival, conflicting readings and memories of this period.[2] In addition to the comparison of various publications we mapped these narratives with an e-mail inquiry asking Hungarian art professionals belonging to different generations and subcultures about the art events of the period that they find the most significant in relation to their own practice.[3] Selecting events for our chronology, we intend to place in parallel the activities of the various generations, as well as events that were held at official (public), professional, and ad-hoc exhibition venues, such as culture houses or clubs, or ones that never passed the planning stage or were banned. Since we were also looking for an answer to the question of how an exhibition becomes a work of art or event, and what can happen at an exhibition, we endeavored to explore the connections between shows that present works of art in a static manner and various actionist and performative practices.

Detour to the Public: A Chronology of Legendary Art Events in the Parallel Culture, 1966–77

In Hungary between the 1950s and ’80s, all public exhibitions had to get permission from the responsible authorities on the basis of a precise list of the artworks, and were fully financed by state institutions. Those tendencies that were not favored by the official cultural politics had to find alternative sites, means of presentation, and strategies of self-organization. A lot of important events, especially in the first half of the ’60s, took place in “airports, club rooms, psychiatric institutes, cultural centers, entrance halls of industrial headquarters, ateliers, private flats”[4]—without any institutional background.

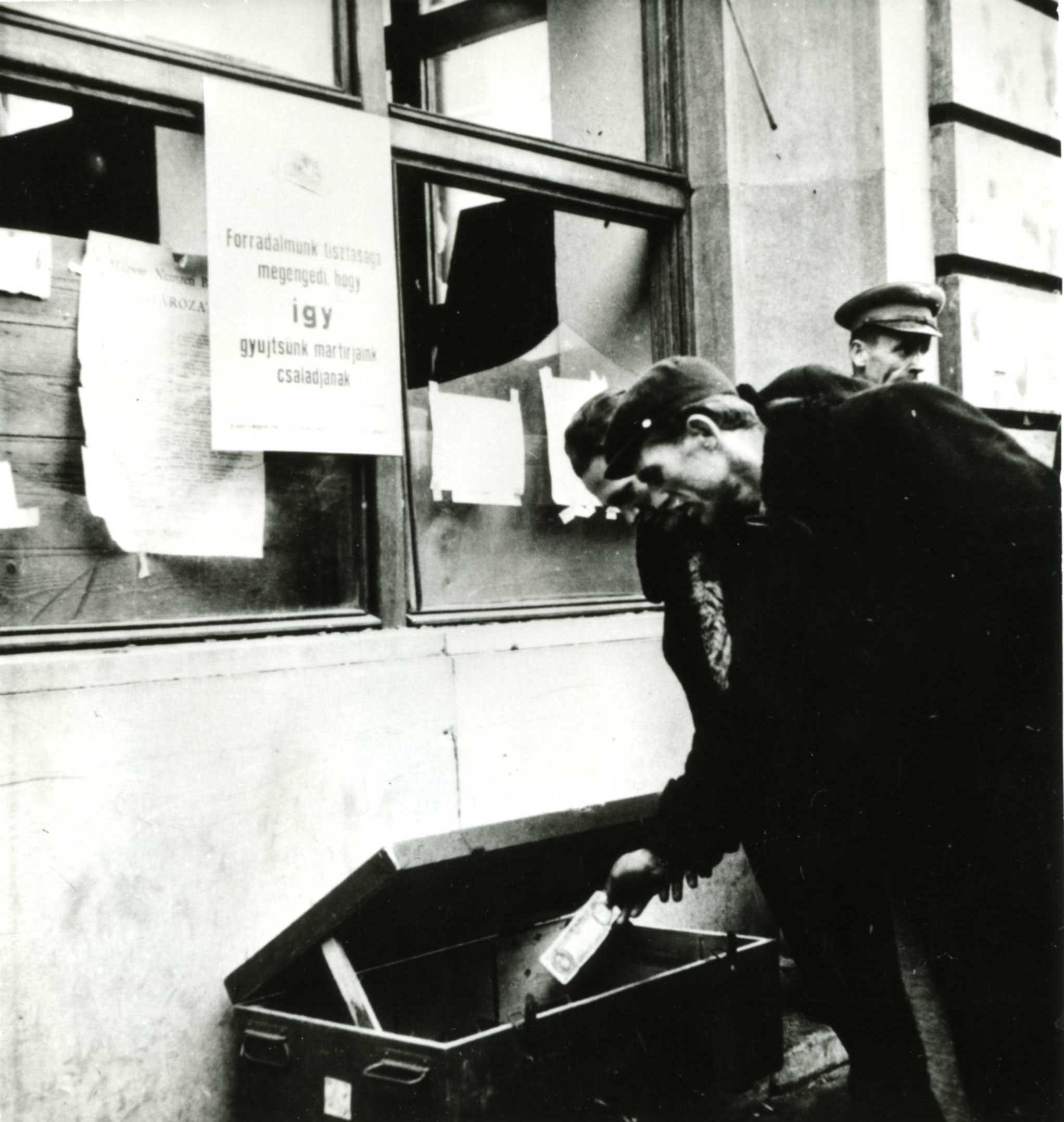

Some actions taking place in the street or in outdoor venues also became emblematic. We have to recall here the one known as “Unguarded Money”. A week after the revolution of 1956 had broken out, open military and red-cross boxes appeared at six central places in Budapest to collect money for the families of victims. A considerable sum was gathered in the streets, and no one took the money out of the unguarded boxes. This event has been quoted many times in the last fifty years as an exceptional moment of human solidarity. On the other hand, in recent art historical writing, this action is connected to Miklós Erdély (1928–86), one of the most important neo-avant-garde artists in Hungary. Erdély was at that time a writer and architect and was involved in the organization of the money gathering. Later, by the time he had become a participant in visual art circles and an active artist himself, he reinterpreted this as an artistic action.[5]

The First Hungarian Happening

The new artistic developments that led Erdély to see this unusual act of solidarity as an artistic act started ten years later with the first happening in Hungary. Most Hungarian and international chronologies that deal with neo-avant-garde art also refer to “The Lunch (in memoriam Batu Khan)” as a point of departure. The 1966 event was organized in the cellar of one of Erdély’s relatives by Tamás Szentjóby (b. 1944) and Gábor Altorjay (b. 1946), who were previously involved in writing metaphysical poetry. Szentjóby traces his shift of attention from metaphysics to physics and actionism back to his struggle to understand his aversion to Pop art. The immediate inspiration came from an article published in the Film Theater Music magazine scornfully describing the happenings of Allan Kaprow, Joseph Beuys, and Robert Rauschenberg.[6] The event was professionally prepared, invitation cards were sent out, photo and film documentation was arranged, and journalists were invited. At the same time the happening was very radical, pushing against the limits of the participants’ and audience’s physical and mental tolerance. Although only fifty to sixty viewers were present, “The Lunch” redefined how art was produced and presented in the following years. The concept of the happening as a dangerous and insane manifestation of disorder coming from the Western world made its appearance also in the nonspecialized press and even in the columns of humor magazines. The secret police filed a report on happenings,[7] which explains why the critical evaluation of the genre was pushed to the periphery of public awareness in the following years.

Self-Financed Avant-Garde

Parallel but independent to the emergence of actionist practices, new possibilities appeared in exhibition making in the second half of the ’60s. In addition to the semi-publicity of flat, studio, and club exhibitions, some official venues also admitted avant-garde artworks. The idea (initiated by György Aczél, minister of culture) came about that exhibitions that cultural policy did not wish to support for ideological reasons should still be provided a venue. This exhibition space was Adolf Fényes Hall, where artists that represented different trends were featured on the condition that they themselves finance their exhibition. The institution of the self-financed exhibition was established by Lajos Kassák’s (avant-garde poet and visual artist, 1887–1967) emblematic exhibition in Adolf Fényes Hall in the year of his death. He could not get permission to exhibit his constructivist works anywhere else in Hungary, and they were hardly known among the younger generation. Thus, this exhibition provided exceptional insight into the master’s later oeuvre and also an occasion for progressive art circles and cultural politics to take up polemical stances. At the same time, it was absurd and embarrassing to expect Kassák—a pioneer of leftist art movements before World War II, who in the ’60s was represented by the most prestigious galleries in Western Europe—to pay all the costs of his exhibition himself.

Self-Organized and Self-Documented Neo-Avant-Garde

While Kassák’s avant-garde work appeared in the realm of tolerated but not supported culture and was accompanied by a catalog and reviewed in the press,[8] the neo-avant-garde artistic practices of the late ’60s rarely achieved such a degree of visibility. The “Iparterv” exhibitions (1968–80) have a particular significance in the history of exhibitions in Hungary in the sense that they provided a common platform and professional management for a new generation of artists engaged in various progressive tendencies from abstract and Informel painting and sculpture to Pop art and actionist practices. The legend of “Iparterv” came into existence at the moment of its happening. Through conscious self-documentation—invitation cards, posters, and a catalog were printed—the loose group provided for its self-historicization. The first exhibition (1968) was preceded by a series of actions and happenings held at the same location in November, organized by Tamás Szentjóby, entitled “Do You See What I See,” and including Miklós Erdély and László Méhes. Two pieces by Erdély and two by Szentjóby were action-readings, the others were actions based on symbolic objects.

The first group show opening in December 1968 was initiated by the participating artists themselves—mostly Gyula Konkoly (b. 1941) and György Jovánovics (b. 1939), who asked the young art historian Péter Sinkovits (b. 1943), who had previously organized smaller exhibitions with some of the participants, to curate them. Sinkovits’s initial plan was to invite Béla Kondor (1931–72) too,[9] who stylistically represented a more traditional idea of art compared to the other avant-garde artists, but in an uncompromising way that was inspiring for progressive art circles. He also intended to include Tamás Szentjóby, but Szentjóby refused categorically for his activity and works to be placed in an artistic context.[10] The first exhibition lasted only a few days, but as László Beke (b. 1944, critic, curator, and art historian) wrote in 1980, “It was the sharpest, most clear-cut event of 1968 within the domain of fine arts in this country. It meant a slap in the face to domestic culture.”[11] For this event a small catalog was printed with a brief introduction by Sinkovits, the longer version of which was only distributed in English for strategic reasons. In this text Sinkovits attempted to claim continuity between the Hungarian masters of the classical avant-garde and the young exhibitors. In 1969 Sinkovits organized a similar collective show again in Iparterv, extending the group with two graphic artists, András Baranyay and János Major, and the participants of the ’68 actions. A year after the 1969 show, they released a samizdat publication with the title Document 69–70. This publication served as an example of samizdat publications with ideologically dangerous content for the education of secret service officers.[12] On the cover of the catalog there was András Baranyay’s group photo of the participants taken before the “Iparterv II” exhibition. The photo communicates the group identity created by the exhibition. In 1980, this group of artists exhibited together at the same venue again, at which time an English Hungarian publication was issued containing a number of studies and also documentation of not only the exhibitions, but also the actions that happened in November 1968. In this book, the authors looked back on the golden age of the neo-avant-garde, writing about the Iparterv legend,[13] which now incorporated not only Pop art and new abstract trends, but actionism too. In December 1988, preceding the political transition, a three-part “Hommage à Iparterv” series was launched at the Fészek Gallery, which conjured up the legend in an altered context.[14] Iparterv became the emblem of a whole generation: the progressive art of the sixties. Moreover, Géza Perneczky derived the paradigm of twentieth-century modernism in Hungary from the emergence of the Iparterv group in his own chronological account of the years 1962 to 1991.[15]

The Exhibition as Artwork: Environments

Exhibitions that presented projects and “environments” that incorporated the entire exhibition space, instead of displaying separate works of art, also had to find venues outside state-controlled institutions. Aside from Adolf Fényes Hall, which was designated for the display of “tolerated” art,[16] such works could only be exhibited in out-of-the-way cultural centers and exhibition spaces outside the capital. The first significant environment in Hungary—according to Géza Perneczky[17]—was György Jovánovics’s (b. 1939) huge plaster sculpture exhibited in Adolf Fényes Hall in 1970 together with István Nádler’s paintings, whose ground plan was identical to the ground plan of the irregular inner space of the hall. Reflecting on the limited publicity of this venue, the exhibition was opened by a fictive radio program that reported on the event amongst the most important international news of the day.

As Jovánovics remembers, his plan was to drop the components of his huge environment made for the exhibition, and oblivion, into the Danube after the exhibition closed in the semiofficial gallery. The actionist Miklós Erdély proposed another solution, so the sculpture was transported to his garden where it became a site for spontaneous actions without an audience, documented by photos.[18] Though no catalog was issued to accompany the exhibition, the photos of the piece and the exhibition opening also appeared in various significant publications and projects: the Dokumentum 69–70 catalog of “Iparterv II,” Gyula Pauer’s index-card project in 1971 that established a collection of progressive art in the form of index cards documenting conceptual works,[19] and the catalog of the 1972 exhibition of six Hungarian artists in the Foksal Gallery. János Sugár (b. 1958), inspired by Jovánovics’s 1970 exhibition, created his first solo exhibition in Adolf Fényes Hall in 1985, which was the location for the shooting of his film Persian Walk. Jovánovics himself also reconstructed the event in a lecture held in 1999, in which he called the opening of the exhibition the best work of his life.[20] Another candidate for the title of first environment was exhibited later the same year by Gyula Pauer (b. 1941) in an off-site cultural house. The “Pseudo Show” accompanied by Pauer’s First Pseudo Manifesto created a sculptural space-illusion within the exhibition space. It was up for only two days and was permitted as a location for shooting János Gulyás’s graduation work at the Hungarian Film Academy. The film documented the opening and destruction of the exhibition too. Géza Perneczky, the reporter, read out texts by Pauer and interviewed the visitors. As evidenced by the film, visitors had to reinterpret their ideas not only about sculpture but about the exhibition genre, too.

The art historian and critic László Beke (b. 1944), who was also interviewed in the film, called the work the first successful environment in Hungary. Perneczky also called the Erzsébet Schaár’s (1908–75) “Street” exhibition in Székesfehérvár an environment. The artist, a representative of a previous generation already active in the ’30s, started to examine the relationship of space and figure, use nontraditional materials, and mix everyday pop and a certain refined, tragic pathos only in the second half of the ’60s. The installation, made of plaster and Styrofoam and representing a street with human figures, filled and recomposed the entire exhibition space. The exhibition was opened by János Pilinszky (1921–81), who read aloud his poems next to certain pieces of the “street,” and was documented from its installation to the opening by the Péter Fitz, János Gulyás, and Pál Vilt’s film Spaces. Schaár created a national mausoleum featuring the most important cultural personalities (using her earlier portrait sculptures) escorted by mysterious female figures. With this work presented in the gallery of the local art museum, Schaár transferred to the public sphere[21] the avant-garde idea of environment.

Independent Venue

The István Csók Gallery in Székesfehérvár, led by Márta Kovalovszky and Péter Kovács, was an exception, in the sense that in the ’60s hardly any exhibition space or gallery could develop a progressive profile.

The organizers and participants of nonconformist events could only sporadically occupy semipublic venues on a few occasions, and then had to move on. In 1971, László Beke organized a large-scale concept exhibition, entitled “Idea/Imagination,” in an A4 folder, as no other location was available for such a show. In 1966, György Galántai, a recently graduated visual artist, found an abandoned chapel in Balatonboglár at Lake Balaton, and decided to open a studio and exhibition space in the empty building. Following a long and testing procedure of acquiring permission, the first exhibition opened in 1970. Initially more traditional, the exhibitions—which also allowed room for tolerated trends—gradually gave way to experimental, performative, and time-based events as well as to projects articulating institutional critique and political statements. When acquiring permission from the authorities for more and more nonconformist exhibitions and events became a hopeless endeavor, Galántai gave up the official procedure and renamed the Chapel Gallery the Chapel Studio, which from this time on could only house nonpublic events.[22] In principal, all events were designated private, although they often dealt with the concept of the public and current issues. From the program of the four summers between 1970 and ’73 we selected five events that, relying on the independence, transitory, and semipublic position of the venue, transformed exhibitions into actions and urged the audience to active participation. On 15 March 1972, the anniversary of the revolution and war of independence of 1848, a couple of hundred people demonstrated against the dictatorship at various places in Budapest. As a reaction, and inspired by Gyula Gazdag’s cult film The Whistling Cobblestone (1971), László Beke announced a call for artworks using grave- and cobblestones, which already had precedents in the photos of János Major (1936–2008).

In April an “Avant-Garde Festival” was organized by Tamás Szentjóby with more than forty participants—poets, visual artists, film directors, musicians, and art historians—who would present readings, screenings, lectures, actions, and more traditional artworks as well. The event was banned after the flyers were printed. In the summer of the same year, Gyula Pauer and Szentjóby wrote and distributed a call for what today might be called an interactive exhibition-happening in the Chapel Studio, which had offered to hold the cancelled “Avant-Garde Festival” there at the same time. The event series and exhibition entitled “Direct Week,” according to the concept formulated in the call for participation, aimed to establish direct contact with the audience instead of exhibiting art objects. It was during this exhibition that Szentjóby presented his action entitled Exclusion Exercise: Punishment-Preventive Auto-Therapy: with a bucket over his head he punished himself for one week, eight hours a day, while also inviting the audience (occasional local visitors and art professionals) to interrogate him. During the “Direct Week” Beke held his slide-lecture on cobble- and gravestones in Hungarian art, which he later called the best lecture of his life.[23] Shortly after the “Direct Week,” the action entitled “Today You Open the Exhibition: Responsibility-Taking Action” was organized by György Galántai and István Haraszty (b. 1934). The organizers’ recollections reveal that they wanted to call attention to the responsibility of the visitors viewing exhibitions without official permission. In Galántai’s Chapel Studio there was also an opportunity for progressive artists from the Eastern Bloc to meet and exhibit their work together (of course without permission). The same summer in 1972, in an event organized by László Beke, Czech and Slovak artists collaborated with their Hungarian colleagues. The exhibition directly reflected on the trauma that had characterized the relationship of the two countries. They ritually tore up a magazine article reporting on Hungarian soldiers who aided in crushing the 1968 Prague revolution, and then all the Hungarian and Czechoslovak artists shook hands. The event was captured in the form of a photomontage.

In the summer of 1973, exceeding the traditional framework of the exhibition, presentations of significant conceptual works, performative and collaborative actions, and performances by representatives of the underground theater organically succeeded one another, creating a continuous festival of progressive art.

One of the first artistic manifestations of Tibor Hajas (1946–80), the internationally recognized poet and action and performance artist, also happened in Balatonboglár in July 1973. He read out his Freedom- Industry Broadcast, Channel 4, and while reading, tied the audience together, then burned the ropes. The text creates a highly ambiguous interrogating voice aimed at the audience, evoking the authoritarian, bureaucratic tone of official public speech, and at the same time, that of the provocative or even irrational rebel who touches upon sensitive political issues excluded from public discussion.

Reflecting on the illusory, artificial, and propagandistic character of the public sphere both in a political and consumerist sense, it demonstrates the difficulties of constituting an authentic, individual voice that can make straightforward public statements. In 1973, the instances of objections raised by the authorities against the Chapel Studio were increasing from all directions. Finally, the progressive artists were evicted a month after Hajas’s action. In the so-called Leaving Action, György Galántai left the chapel with a prop from an underground-theater action: a sign reading “Friendly Treatment.”

Non-art as Art

From the early ’70s onwards, stricter control over progressive practices endangered individual careers, too. At the end of 1975, Tamás Szentjóby was expelled from the country, as his artistic activities had been deemed overly provocative by the cultural authorities (he had been observed by the secret police since the ’60s). We selected three significant events from his activity in the ’70s in Hungary that introduced new genres and also draw attention to two important venues of the period.[24] The first was an event hold at the University Stage, which was a venue that housed various conventional and progressive practices in the ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s, from pop music to theater, screenings, and fine-art actions.[25] Szentjóby performed several actions there, most notably “He Ropes the Cow with Rope”, a didactic action-reading in 1973. The lecture, taking the structural change in wage-distribution initiated by Che Guevara as an example, describes how traditional culture based on the appreciation of rare talent could be deconstructed. Using language, which is stated to be the scheme of life, in a nonconformist way, “we recognize that we are free, and we are capable of reorganizing and regrouping the elements of life.”[26] The text read out loud was accompanied by absurd, conjurer-like, didactic actions involving a pigeon, a cat, and a dog tied to various objects. Prior to his departure, Szentjóby organized an exhibition collecting together his works produced between 1966 and 1975 for his own retrospective, in a way, at the Club of Young Artists. The Club of Young Artists was an institution (with community exhibition spaces and a pub) operating in a villa between 1960 and 1998, and was the haunt of followers of underground culture, but also of informers. It had a progressive period in the ’70s when it provided a location for semipublic neo-avant-garde exhibitions, pop concerts, educational lectures, readings, and screenings. In this exhibition organized and initiated by Szentjóby himself, he presented about 150 pieces—visual poetry, objects, environments, photos, and documents. Displaying framed concrete poems, action objects, and documents of his actions, he invented an archival methodology with which new progressive practices could be incorporated in the format of an exhibition. Later in the same year, Szentjóby also performed a lecture, “Make a Chair! (Hommage à George Brecht)”, in the Club of Young Artists, using only the most traditional educational device—the blackboard—as a prop. In this lecture he proposed the imperative “Make a chair!”—the symbolic object of strike—to go beyond the “Use a chair!” imperative in George Brecht’s events and the “Look at the chair” imperative of Duchamp’s readymades. The International Parallel Union of Telecommunication’s (IPUT, superintendent: Tamás St. Auby) Subsistence Level Standard Project 1984 (SLSP1984W),[27] whose fifth phase is still in force, was first announced with this lecture, which was repeated in 1977 during documenta 6 in Kassel, within Joseph Beuys’s Free International University.

An Invisible Female Position

The same venue, the Club of Young Artists, housed the “Nude/Model” exhibition of Orsolya Drozdik, a member of post-conceptualist artist group Rózsa Circle that worked together and organized collective actions and exhibitions between 1975 and 1977. This circle appeared at the end of the ’70s with young artists raising new issues like self-management or gender relationships. Organizing collective actions in a bar, they adopted the language and genres of conceptual art, but they were much more concerned with their own identity as individuals and artists than the earlier generation of the neo-avant-garde. Drozdik’s “Nude/Model” reflected on the male-centered perspective of traditional art education. Her week-long performance involved drawing a female nude—the most usual activity of traditional art education—and presenting this activity as an exhibition, a sight for contemplation. The visitors could not enter the room but could only look in through a gauze cover that blocked the entrance. Drozdik invited various male artists and an art historian to open her “exhibition” each day. In addition to the consciously assumed female position, the critique on art history and education also indicates a new, postmodern approach. In 1978, Drozdik emigrated to the Netherlands, and then to New York, where her intuitive approach of a woman artist unfolded in line with feminist theories.

Several other artistic events happened in this period that renewed the genre of the exhibition and the norms of exhibition making. We could mention street actions, samizdat art publications, and work groups engaged in educational projects, which appeared as alternatives to the presentation formats tied to the exhibition space and cultural institutions. To bring this discussion to a close, we may take one such example, Dóra Maurer and Miklós Erdély’s “Creativity Exercises.”[28] The course functioned from 1976–77 at the Ganz Mávag Cultural Center, and instead of the individual, artwork-centered creative process, introduced an alternative educational model that was based on community experiences and the deconstruction of traditional art education. The study circle later continued under a different name and in a new location, finally transforming into the INDIGO group, which made its appearance at a number of exhibitions at the end of the ’70s. Maurer documented the workshops and then in the ’80s, she edited the footage into thematic sections at the Balázs Béla Studio producing a film entitled “Creativity-Visuality”.

We have focused on a period that brought radical change in exhibition making through direct reaction to international trends as well as to the local reality on a social, political, and cultural level. The chosen case studies offer insight into all those historical conditions that determined how art could be presented to the public in Hungary, from the apartment exhibitions and legendary events of the ’60s to the emergence of postmodern tendencies in the late ’70s. The traditional objects of art produced in the period have been more or less integrated into the international history of art through collections, publications, and retrospective exhibitions, while the events and exhibitions still compose an invisible history. Here we present a collection of documents that need committed and critical readers to make a fragment of this history visible.

Term used for semi-official and illegal cultural practices constituting a parallel public sphere.

Dóra Maurer, “Attempt at a Chronology of the Avant-Garde Movement in Hungary 1966–80,” in Künstler aus Ungarn, exhibition catalog (Kunsthalle Wilhelmshaven, 1980); Hungarian Art of the Twentieth Century: Years of Dénouement around 1960 (Székesfehérvár, 1983); Hungarian Art of the Twentieth Century: Early and New Avant-Garde (1967–1975) (Székesfehérvár, 1987); Hungarian Art of the Twentieth Century: The End of the Avant-Garde (1975-1980) (Székesfehérvár, 1989); The Sixties: New Trends in Hungarian Visual Art (Hungarian National Gallery, 1991); “Context Chronology: Politics, Science, and Art from 1963 to 1989” (only in Hungarian), http://artpool.hu/kontextus/kronologia/1963.html; “The Chronology Attempt for the Avant-Garde Art in Hungary between 1966–1980” (only in Hungarian), http://www.c3.hu/collection/koncept/index2.html; “Portable Intelligence Increase Museum,” established by the NETRAF (Neo-Socialist Realist International Parallel Union of Telecommunications’ Global Counter-Art History Falsers’ Front), agent: Tamás St.Auby.

A selection of answers can be read in our publication Parallel Chronologies (tranzit.hu, 2011).

László Beke, “12 years Iparterv,” in Iparterv 68–80 (Budapest, 1980), VIII. “The salons of Pal Petri-Galla [1922–76] and Gyula Grexa were not only frequent meeting places for writers, painters, musicians, and art enthusiasts who gathered there to listen to music and discuss cultural events, they also served—primarily in Petri-Galla’s case—as venues for exhibitions, art debates, and readings. […] Dr. László Végh [radiographer] who worked both in theory and practice—in the areas of concrete and electronic music—made appearances with his group of young actionists [Tamás Szentjóby, Gábor Altorjay].” Ádám Tábor, Váratlan kultúra (Balassi Kiadó, 1997), 22–23.

Miklós Peternák, “Beszélgetés Erdély Miklóssal 1983 tavaszán” [Interview with Miklós Erdély in Spring 1983], Árgus 5 (1991): 76–77.

Mária Ember, “Happening és antihappening” [Happening and antihappening], Film Színház Muzsika (13 May 1966).

See http://exhibition-history.blog.hu/2009/07/February/police_report.

In English: Éva Körner, “Kassák the Painter in Theory and Practice,” New Hungarian Quarterly 28 (1967): 107–12.

Péter Sinkovits, “Chronology,” in Iparterv 68–80, 10.

Sinkovits, “Chronology,” 11.

Beke, “12 years Iparterv,” IX.

Az ellenség tanulmányozása [Studying the enemy], 1972. Preliminary textbook for the police academy written by Ferenc Gál, police commander.

“Iparterv became a legend, though there is hardly anyone who knows anything about it. The young generation wants to face the myth.” Beke, “12 years Iparterv,” p. II.

Iparterv also embodied the art of opposition. After the political transition of 1989, most of the participants were invited to teach at the Hungarian Academy of Arts, their oeuvres were rehabilitated with retrospective exhibitions organizer institutions, following from that time on professional standards and not only those of cultural politics.

Géza Perneczky, “Produktivitasra ítélve? Az Iparterv-csoport és ami utána következett” [Doomed to productivity.:The Iparterv Group and what came after], I–II, Balkon 1–3 (1996): 5–22, 15–28.

According to the cultural policy introduced in Hungary by György Aczél in the late ’60s, cultural production was classified into three categories: supported, tolerated, and prohibited.

Perneczky, “Produktivitasra ítelve?,” Balkon 3: 24.

György Jovánovics, “Emlék-képek,” Orpheus 4 (1992): 92–115.

Pauer made this collection for “Idea—Imagination” (1971) by László Beke, which was an exhibition on sheets of A4 paper and today is an important document of Hungarian conceptual art. László Beke, Elképzelés. A magyar konceptműveszet kezdetei. Beke László gyűjtemenye, 1971 [Idea/Imagination. Beginnings of Hungarian Conceptual Art: The Collection of László Beke 1971] (Nyílt Strukturák Művészeti Egyesület OSAS-tranzit.hu: Budapest, 2008).

György Jovánovics, “The best work of my life …” (lecture, Artpool Art Research Center, Budapest, 1999).

However, according to Géza Perneczky, this exhibition was not juried either as the curators found a legal loophole permitting them to avoid this procedure. Perneczky, “Produktivitásra ítélve?,” Balkon 3: 25.

The history of the Chapel Studio was published in the book Törvénytelen avantgárd. Galántai György balatonboglári kápolnaműterme 1970–1973 [Illegal Avant-garde, the Balatonboglár Chapel Studio of György Galántai 1970–1973], eds. Júlia Klaniczay and Edit Sasvári (Artpool–Balassi, Budapest, 2003).

Ibid., 141.

Szentjóby, spelling his name differently (St. Auby), moved back from Switzerland to Hungary in 1991.

A big-scale Fluxus concert organized by Szentjóby and Beke in 1973 was canceled, although the program guides had been printed. The program was reconstructed twenty years later, when a multimedia documentation of the event was created.

Szentjóby also made an ironic remark in the text referring to the authorities observing him being puzzled by the unconventional use of language.

The mission of the project is that everyone be guaranteed the minimum subsistence level standard.

Kreativitási gyakorlatok, FAFEJ, INDIGO. Erdély Miklós művészetpedagógiai tevékenysége 1975-1986 [Creativity Exercises, Fantasy Developing Exercises, and Interdisciplinary-Thinking: Miklós Erdély’s Art-Pedagogical Activity], complied by Sándor Hornyik and Annamária Szőke, ed. Szőke Annamária. (MTA Művészettörténeti Kutatóintézet. Gondolat Kiadó. 2B Alapítvány. Erdély Miklós Alapítvány, Budapest, 2008). The publication has an English summary at the end.