The Conference Comrade Woman – Art Program (On Marxism and Feminism and Their Mutual Political Discontents)

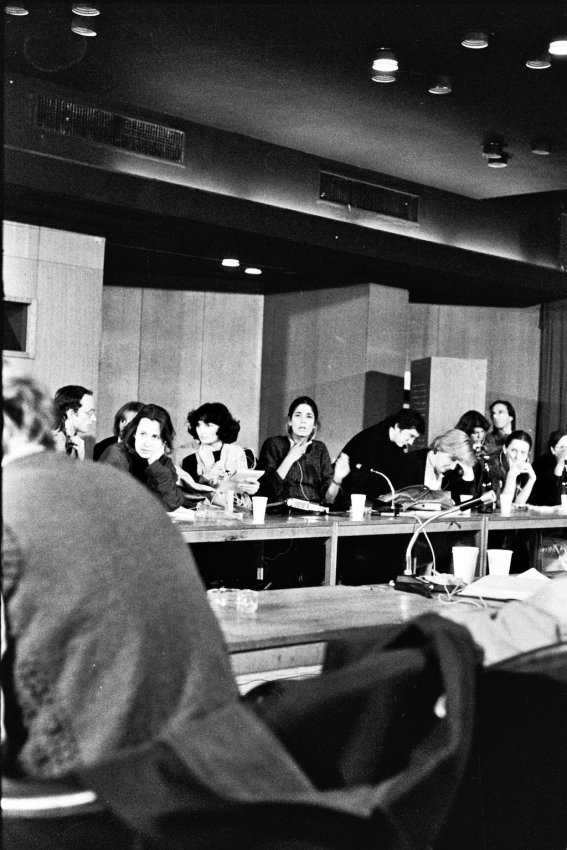

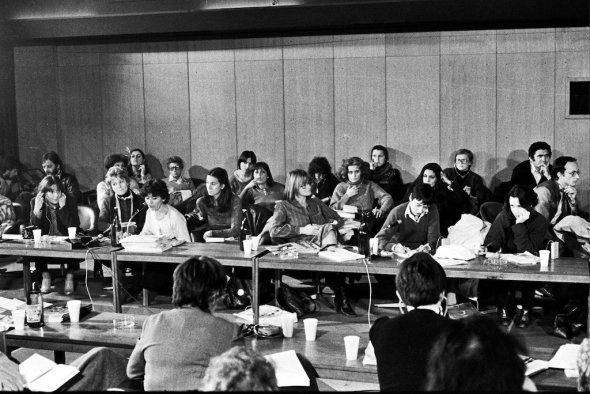

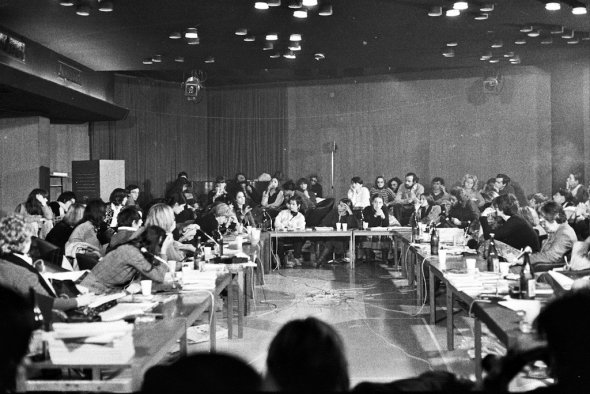

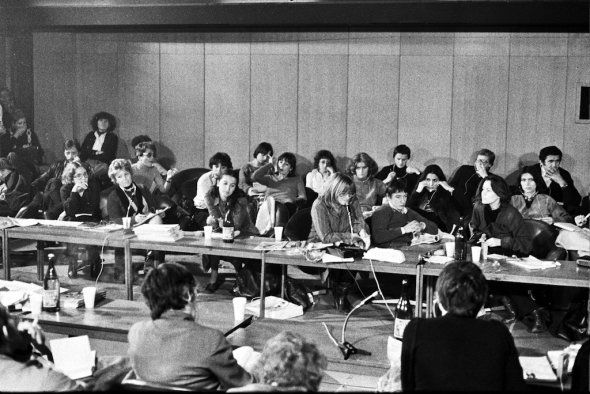

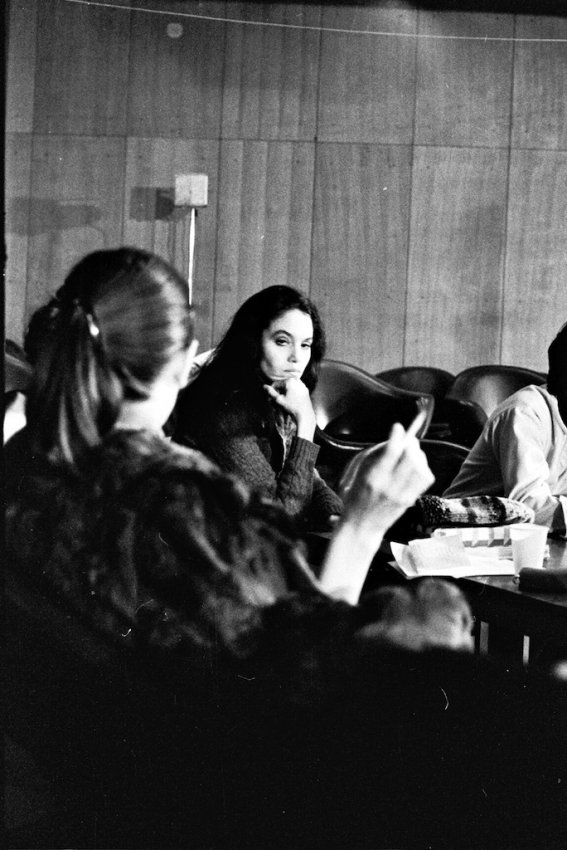

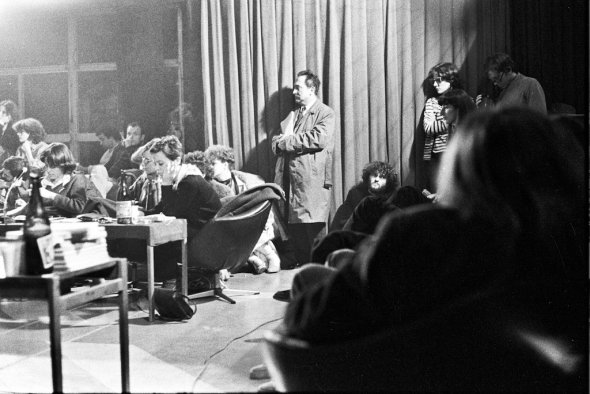

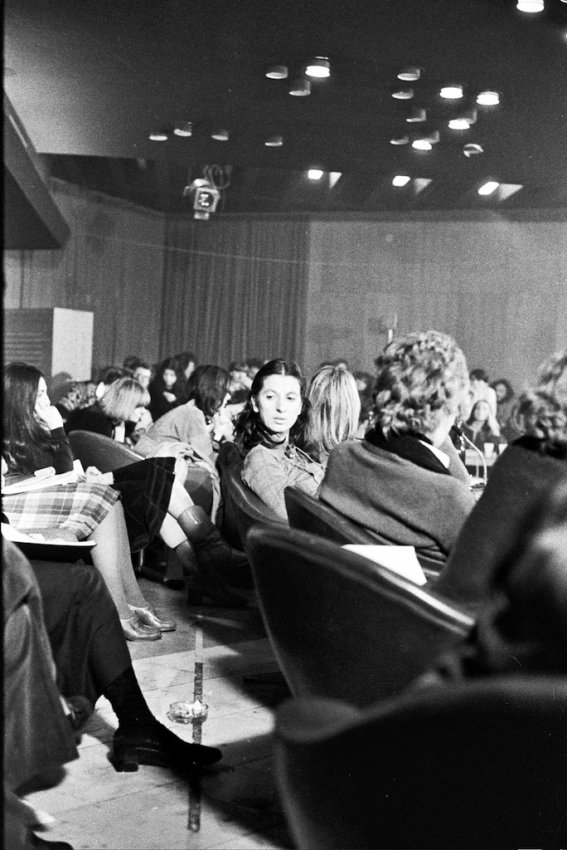

The international conference Comrade Woman: Women’s Question – A New Approach? (Drug-ca Žena: Žensko Pitanje – Novi Pristup?) took place at the Student Cultural Centre (SKC), Belgrade, in 1978. It was the first autonomous second-wave feminist meeting in former Yugoslavia, and beyond—the first conference of this kind initiated in non-Western-European context, and in a socialist country. Comrade Woman gathered a number of significant feminist theorists and artists from both sides of “the curtain,” and especially from various different cities in Yugoslavia. The discussions that took place in the different venues and spaces of SKC were accompanied by a thematic art program of exhibitions, films, and video-art screenings.

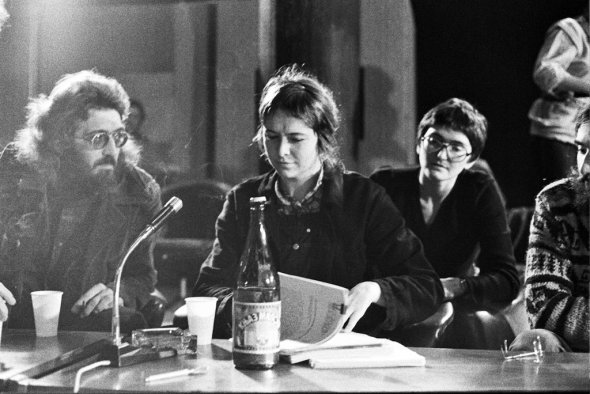

The event was initiated by Žarana Papić, a young feminist and anthropologist from Belgrade, who curated the conference program in collaboration with Dunja Blažević (who was then the director of SKC), and was predominantly focused on social-political issues. The panel discussions were developed in three thematic threads: 1) women, capitalism, social change; 2) women’s culture; 3) women, capitalism, revolution.

The closing session called Position(s) of Woman in the Self-managed Socialist Society was dedicated to specific local issues and feminist struggles in the Yugoslav political context. According to the recollections of participants, the initiation of the conference was also attributed to several academic intellectuals who were colleagues of Papić: Nada Ler-Sofornić, Vesna Pusić, Lidija Sklevicki, and Rada Iveković.

The visual arts program that accompanied the conference was curated by Biljana Tomić (who was head of the SKC gallery at the time) and Dunja Blažević, with the assistance of a younger art historian Bojana Pejić. Before Comrade Woman, the only artistic event taking place in SKC that could be explicitly designated as feminist was the discussion Women in Art,[1] organized within the fourth edition of April Meetings – The Festival of Extended Media in 1975 (the year was celebrated as the International Year of Women worldwide).[2]

The exhibition program included two documentary displays. One was The Yugoslav Woman in Statistics (Jugoslovenska žena u statistici), conceptualized through the selection of different data “portraying” the position of women in Yugoslavia; interestingly enough, the data was collected from official state media, such as the annual statistics report (Statistički godišnjak) and the similarly titled publication A Woman in Statistics of Yugoslavia (Žena u statistici Jugoslavije), published by the state organization called the Conference for Social Activity of Women (Konferencija za društvenu aktivnost žena)—the main organ of the party for discussing women’s issues in the official political context. Another documentary display was presented under the title The Sexism That Surrounds Us (Seksizam oko nas), comprising a selection of excerpts from Yugoslav press that illustrated the thesis about women being dominantly perceived as sexual objects, and their social role being reduced to motherhood and housekeeping, despite the nominally progressive, egalitarian and socialist tendency of Yugoslav society at the time.

The exhibitions included a presentation of illustrations by the French cartoonist Claire Bretécher, which were also occasionally published in Zagreb-based women review Modni Svjet (Djurdja Milanović was the editor in chief, and one of the participants of the conference), and Portraits of Women, an exhibition by Goranka Matić that presented in the SKC gallery.

The exhibition by Matić included more than forty photographs of women in the format of black-and-white portraits (50 x 60 cm), which were shown along the gallery walls. The process of photographing was conceptualized as a docu-fiction—in parallel to being photographed, women could decide how they would like to be presented by answering the following four questions: How old are you?; What name you would like to have/get?; Where would you like to live?; What occupation do you desire? Their answers accompanied the portraits in the form of photo captions. The “sample” of photographs presented women at various stages of life, with different experiences, professions, and cross-cultural backgrounds. The youngest participants were in the stage right after their first menstrual cycle, while the oldest participants were sometimes over eighty years old. In a conversation with Matić, she revealed that the oldest “commrade woman”, who was photographed selling fruits on the Green Market, offered quite a curious answer to the question of employment, stating that she preferred to be occupied by nothing—that her desired “job” would be to just sit and rest.[3] This particular “piece of data” or personal statement, among other things, also reveals the specific character of Matić’s questionnaire—the fact that it was about desires and imagination of a “better world,” rather than about the “scientific objectivity” of the data collected. The data presented was almost entirely fictional and was meant to address the actual desires of the subjects of the questionnaire. It was only the information about the participants’ age and the personalities that emerged from the photographs that stayed on the side of documentary. Matić, today one of the most important photographers working in Belgrade and exhibiting internationally, was at the time a young art historian who came up with the concept, and realized the exhibition in collaboration with Nebojša Čankarović, who was employed as the photographer of SKC at that time. In that sense, the exhibition can be also explored in terms of a curator-artist relation, or in the context of “delegated photography” and participatory art/curatorial practice. Matić is also being photographed and represented in the frieze of the Portraits of Women. Her fictional name was Ira Fasbinder, and she presented herself as the thirty-year-old Madam of the Brothel in Budapest. In the photo we see Ira, a young woman with short hair, dressed in a tie, a neat shirt, waistcoat, and jacket, with a cigarette hanging from the corner of her mouth.[4] Others who were photographed included some of the participants of the Comrade Woman conference, among them Dunja Blažević, Ljubica Stanivuk, and Žarana Papić.

The film and video screening event included presentations of following works: La Roquette, Prison de Femmes (1974) by Nil Yalter, Judy Blum, and Nicole Croiset; The Apple Game (1977) by Vera Chytilová; The Living Truth (1972) by Tomislav Radić; The Night Porter (1974) by Liliana Cavani; Aggettivo Donna (1972) by Rony Dapulo; Il Rischio Vivere (1977) by Annabella Miscuglio and Anna Carini; Talking about Love (1974–75, video) by Jasmina Tešanović; Fughe Lineari (1975), Puzzle Therapy (1976), Rony, and Paola by Annabella Miscuglio; La Bella Addormentata nel Bosco (1978), Mio padre amore mio (1976), and Aborto: Parlano le donne (1976) by Dacia Maraini.

Papić edited the preparatory seminar materials in Serbo-Croatian and English, which included texts by Marxist social feminists (Alexandra Kollontai, Evelyn Reed, and Sheila Rowbotham), feminist-Marxist theoretical psychoanalyists (Shulamith Firestone and Juliet Mitchell), theorists of sexual difference (i.e., Luce Irigaray), and a series of texts on the emergence of the feminist movement in Italy. The reader also included essays by Yugoslav feminists previously published in periodicals such as Vidici or Žena.

The conference Comrade Woman opened up a cluster of important debates facing the long (often conflictual) history of Marxism and feminism, especially within the socialist context, including both the history of people’s struggle for emancipation and of official state politics in real socialist countries. In the Yugoslav context, the issue of women’s liberation is considered to be solved within the paradigm of universal emancipation; for example, the feminist-communist organization Women’s Anti-Fascist Front, or AFŽ, was self-abolished in 1953, claiming that their “historical task” was being performed and that the specific “women’s issues” were delegated to the state party organization called the Conference for Social Activity of Women—in general, the issue of the liberation of women was considered to be “solved.” However, in Yugoslav context the difference between the nominal political theory or state propaganda in favor of women’s rights, and the actual realization of these ideas in everyday reality remained strikingly visible. Despite of social state investments in women’s liberation through different supports such as education, equal right to work, organized support for reproductive and family care (free medical service, kindergartens, and education), the Yugoslav socialist culture remained essentially patriarchal —the “bourgeois morality,” with all its taboos and constraints remained to loom on the path of “universal emancipation.” In that sense, the conference resulted in certain conflicts between the “official” and “alternative’ spheres,” between the so-called state and autonomous feminisms. In this particular case, “autonomous feminism” was accused by the state media for anarcho-liberalism and new-leftism as reactionary and politically confusing “imports” from the Western capitalist democracy. The debates were conducted in different media and educational contexts, most vividly in the Belgrade magazine Student, which regularly followed and reviewed the activities of SKC.

Critical positioning toward the Yugoslav “state feminism” at the Comrade Woman conference is performed from the similar angle as was the artistic critique of the “state art’ in October 75 and many other socially engaged SKC projects—Comrade Woman was considered as a form of “internal critique” of the Yugoslav system, stemming from the feminist, but also from socialist premises.

Some aspects of this critical atmosphere were captured in the reportage of the conference by the feminist journalist Vesna Kesić, which was published in the Zagreb-based magazine Start, where she talks about solidarity between young Yugoslav feminists and feminist activists in the West. Kesić writes: “Their path into feminism is mostly similar to our own. They rose together with the men in the 1960s as the members of left students’ movements, as the members of western communist parties or anti-parliamentary left activists. But soon they felt that despite the common struggle for universal emancipation of the humankind and human goals they remained neglected in the theory and practice of these movements. Despite of the declarative equality between men and women which is part of all existing leftist political programs, they confronted with the male intellectual left which suffered from almost identical forms of sexism, of masculine-chauvinist consciousness and non equality that traditionally dominated in bourgeois order.”

Document: The need for a new approach to the women question (the summary in English of the conference plan)

Participants in the discussion Women in Art were: Gislind Nabakowski, Urlike Rosenbach, and Katherina Sieverding (Dusseldorf); Natalia LL (Wrocław); Iole de Freitas (Milan); Ida Biard, and Nena Baljković/Dimitrijević (Zagreb); Irina Subotić, Jasna Tijardović, Jadranka Vinterhalter, Biljana Tomić, and Dunja Blažević (Belgrade).

April Meetings were established on the occasion of April 4, 1972, also Students’ Day in Belgrade. In the first years, between 1972 and 1977, the festival carried the name Festival of Extended Media with the goal of overcoming the existing institutional borders between different arts, and fostering interdisciplinary approach and experimental character of New Art.

The facts and details related to the exhibition Portraits of Women were “reconstructed” in a conversation I had with Goranka Matić, on the occasion of writing of this article.

The description is taken from the transcript of the 40th Anniversary Celebration of the Conference Comrade Woman, organized in Sarajevo by Foundation CURE in 2008. The transcript, edited by Danijela Dugančić-Živanović, was published in the special issue of the journal Pro-Femina, and was edited by Jelena Petrović and Damir Arsenijević in 2011.

Date: October 27–29, 1978

Participants: Helen Roberts, Parveen Adams, Jill Lewis, Diana Leonard-Barker (United Kingdom); Naty Garcia, Christine Delphy, Catherine Nadaud, Catherine Millet, Françoise Pasquier (France); Nil Yalter (France-Turkey); Ewa Morawska (Poland); Judit Kele, Lovas Ilona (Hungary); Dacia Maraini, Carla Ravaioli, Chiara Saraceno, Anne-Marie Boetti, Manuela Fraire, Annabella Miscuglio, Ida Magli, Adele Cambria (Italy); Alice Schwarzer (West Germany); Dramušić, Rada Đuričin, Dragan Klajić, Anđelka Milić, Miloš Nemanjić, Živana Olbina, Borka Pavičević, Vesna Pešić, Milica Posavec, Vera Smiljanić, Vuk Stambolović, Karel Turza, Ljuba Stojić, Dunja Blažević, Jasmina Tešanović, Biljana Tomić, Danica Mijović, Žarana Papić, Goranka Matić, Bojana Pejić (Yugoslavia–Belgrade) Vesna; Ida Biard, Gordana Cerjan-Letica, Nadežda Cacinović-Puhovski, Slavenka Drakulić-Ilić, Ruža First-Dilić, Božidarka Frajt, Đurda Milanović, Vesna Pušić, Lidija Sklevicki, Jelena Zupa (Yugoslavia–Zagreb); Mira Oklobdžija, Slobodan Drakulić (Yugoslavia–Rijeka); Katalin Ladik (Yugoslavia–Novi Sad); Nada Ler-Sofornić, Zoran Vidaković (Yugoslavia–Sarajevo); Silva Menžarić (Yugoslavia–Ljubljana); Rada Iveković (Belgrade–Rome).

Location: Student Cultural Centre (SKC), Belgrade